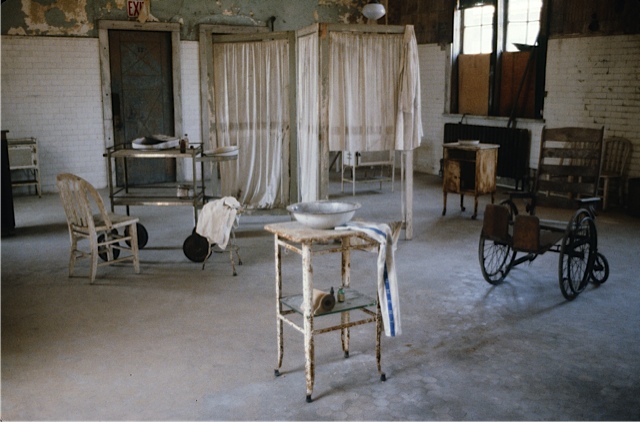

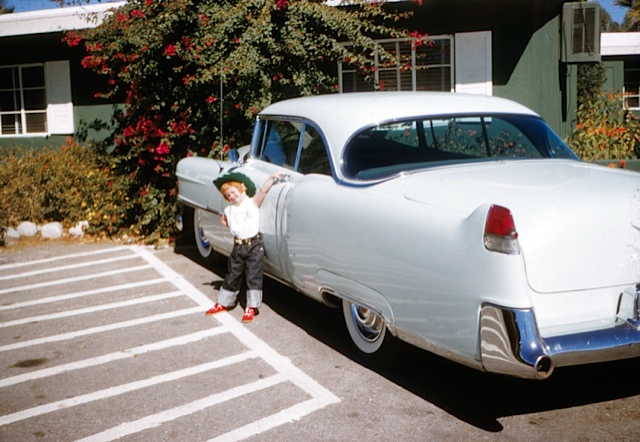

In 1959, following her cardiologist’s orders, my mother took to her bed for a year. Her arteries were found to be compromised (later determined to be angina), with the concomitant restricted blood flow, necessitating dramatic measures of treatment. These were the antiquated days of medicine, apparently. Leeches and cupping were no longer in vogue and bypass surgery was in its developmental stages. Bed rest for cardiac patients seemed to be the prescription of choice. It had only taken three months of hospitalization for my mother’s doctor to arrive at a diagnosis and the resulting prognosis. While my mother languished in Peralta Hospital for an entire season and my father fretted over how to care for his 8-year-old hand-wringing daughter, family friends took action and scooped me up, brought me to their jewel-box, split-level house in the Oakland hills, and plopped me down in the spare twin bed in my little friend’s bedroom. There I ached to see my mother, agitated over my father’s unpredictably timed visits to see me, and felt conflicted that the Leysers’ house was so much cooler than our suburban ranch-style I wasn’t sure I wanted to leave this modern house and vivacious family. The views from their enormous plate-glass windows were stellar; plus they had an entire playroom in the basement complete with a small stage for all our theatrical production needs.

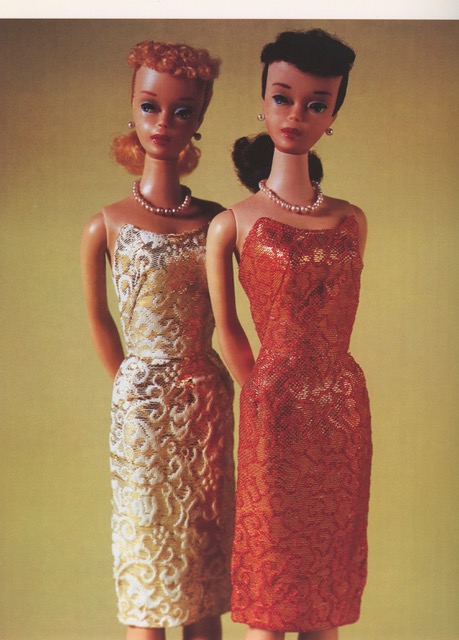

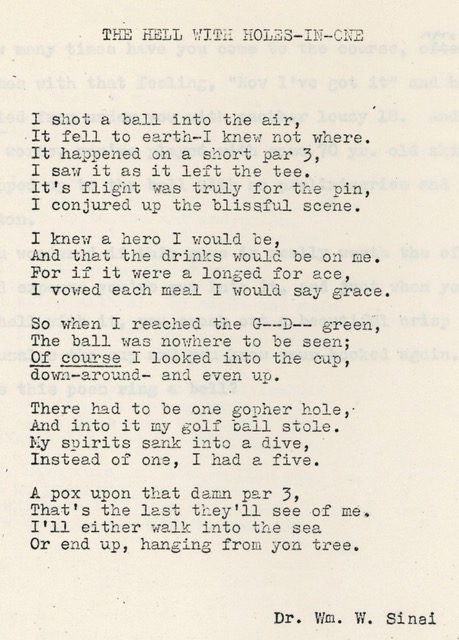

My parents and I eventually reunited. None of us returned home whole probably because the linchpin in our family unit had been irreparably damaged; my mother’s “condition” frightened us all in ways that were never discussed. Anxiety prevailed but was tamped down by my mother’s humor and my father’s doting attention to “his girls.” I threw myself into hours of Barbie-doll fantasy play emerging from my room only when paged to do so by my mom. Only my mother took her time regaining her bearings once she returned home. The resting part of her doctor’s bed rest decree, in fact, resulted in the three of us moping around lethargic and unmoored. Her world had shrunk to a reasonably sized bedroom mercifully outfitted with a Zenith portable black-and-white T.V. and a remote control dubbed the Space Command by the manufacturers. My mother called it Sputnik. My father never tired of recounting how he had won the T.V. in a golf tournament thanks to his eagle on that par-5 hole. What auspicious luck, he would say, morphing our family’s precarious predicament into a light-hearted fable.

For her year in bed, my mother costumed herself with as much panache as she brought to her business outfits and her social ensembles. I was called upon to reorganize her closet and dresser drawers according to her directives reflecting the new clothing guidelines. We moved her work wardrobe to the back of the closet along with her high heels and dinner plate-sized hats. She folded up her oversized sunglasses into their quilted sleeves. She ironed her gloves with a stroke of her hand before tucking them into a drawer, and she placed her enormous purses in the only spot big enough for storage: the laundry hamper.

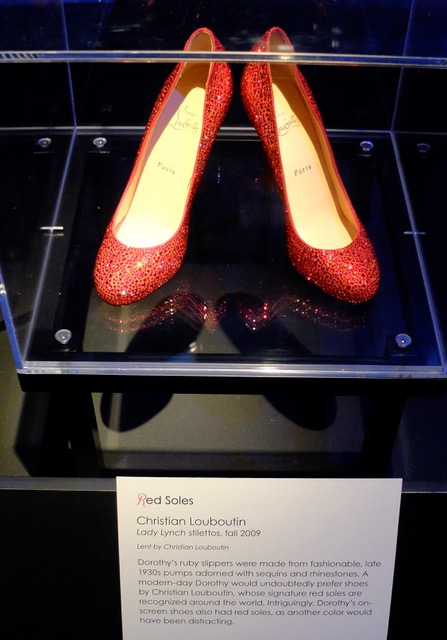

What she kept accessible were her foundations…that is, underwear. I will elaborate further: girdles, garters, and nylons (aka hose). As she had spent her adult life wearing high-heels, with a more recent penchant for backless shoes, she satisfied her compulsion to mimic life on the outside by wearing peep-toed slides that she insisted were bedroom slippers. Some had plastic glittery straps; others were adorned with pom poms on the toes. None were meant to hit the pavement but placated my mother’s need to keep her fashion bar high. In fact, her heart was unpredictable enough that she became disinclined if not downright scared to leave the house in case her angina attacks required more than a lie down. More than once she had collapsed on the sidewalk or inside a store resulting in an impressive shiner on her face and another time a broken wrist. Suddenly, her disease was visible to all. Vanity prevailed, agoraphobic fears took hold and both resulted in a complete change of wardrobe and accessories. But how to procure new threads when on house arrest?

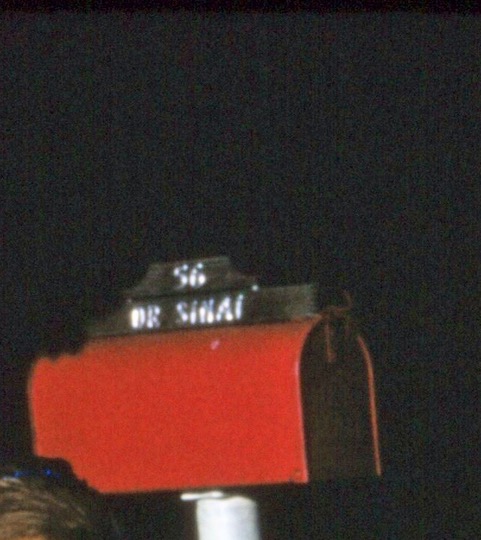

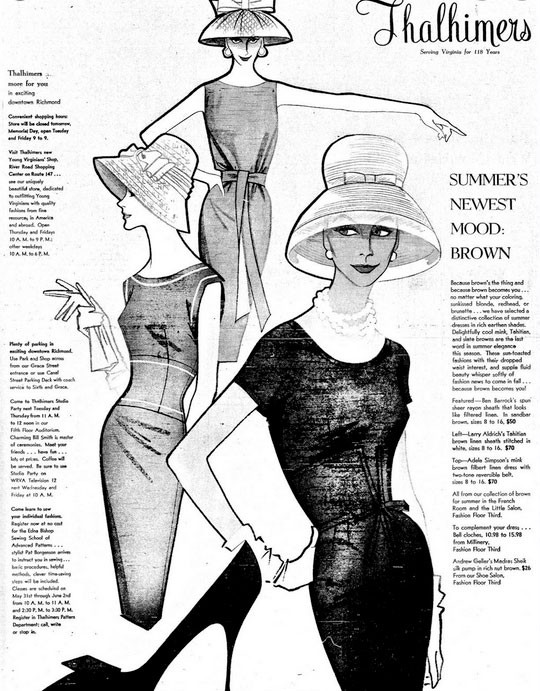

Way back then, on-line anything suggested the backyard clothesline or perhaps the telephone’s party line. It certainly didn’t refer to shopping. That’s what the newspaper ads were for. Deep within the body of the daily paper were the women’s pages—Dear Abby columns, recipes, Helpful Hints from Heloise—all to entertain, inspire, educate and occasionally repudiate the homemaker. Buried adjacent to these literary treasures were advertisements, boxed-in and bordered with heavy, bold lines. Found within was an ad for a specific shop’s dress, sweater, coat, etc. rendered to hit all the right buttons. Lovely young buxom women illustrated with bouffant flips that would make Patty Duke envious. If my mother were scanning the paper for some recreational shopping she only had to espy the garment on the model drawn with a tiny waist, slim gams, and thin arms animated in some way – in her pockets to illustrate the dress’s movement or with a purse daintily hanging from her wrist—to then imagine owning it. Shopping commenced while Sputnik patiently rested on my mom’s lap. Overnight deliveries unheard of, we giddily waited for the parcels to arrive. Generally speaking, the arrival of the daily mail induced palpable excitement. It was a bit of a schlep from the front door, across the yard, and through the garden gate to the mailbox which stood sentry on the curb. The mailman would raise the toy-sized red-metal flag signaling that the box had been restocked with our daily haul of letters, bills, and magazines. Parcels, though, received the royal treatment. These were the post-Pony Express but pre-Amazon days. The mailman (and they were all men) didn’t unload a flotilla of packages as we have now come to expect; rather he brought the long-awaited carton, wrapped in brown paper, and often tied with string, to the front door and rang the bell waiting for the recipient to gleefully accept the goods. Not so very different than the personalized and enthusiastic speedy delivery service offered by Mr. McFeely to an ever-exhilarated Fred Rogers. Less chatter but similar gusto. If my mother was trussed up in one of her chenille robes she might accept the parcel, otherwise I was advised to open the door, get the goods, and to remember to say thank you.

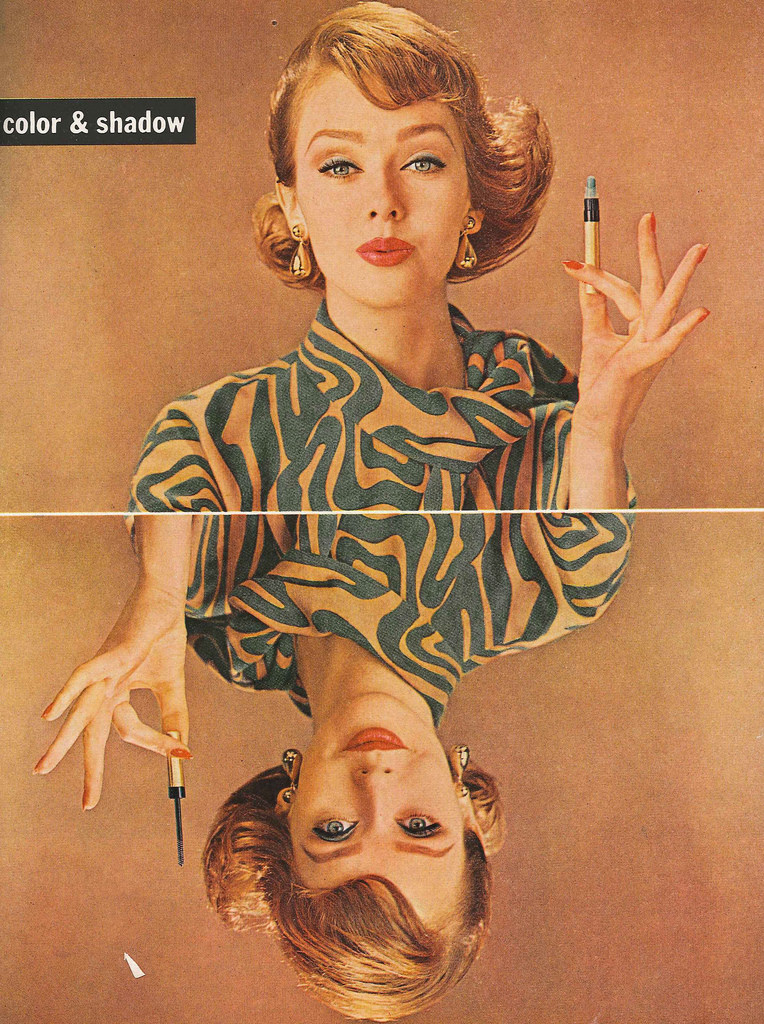

First the bed jackets arrived. These were often ¾-length sleeved, button-down cardigans of a sort. Often there were silky bows that fastened at the collar; others had no closure but apparently kept the chill at bay. The satin ones were my favorites and probably my mother’s too because of the way the fabric caught the light and made the pseudo-jacket seem almost like party wear. Extravagant and useless, like so many fashion statements, they looked debonair whether worn or nonchalantly tossed atop the bed.

Growing bored with skimpy, ersatz party jackets, the next mail-order packages to arrive disgorged fluffy, substantial robes all of which were particularly lavish. Heavy and full length, some terry cloth and others chenille, she draped these behemoths over her frail shoulders when her needs required her to leave the bedroom. Bathroom visits, the occasional trip to the mailbox or even the front door required modesty but more crucially the jaunt was an excuse for dressing up, as it were. I’ve always been a robe wearer myself, but procuring them is getting more arduous and depressing. My last robe purchase, in fact, found me in the dimly lit recesses of Macy’s 2nd floor where each lonely, homely robe hung askew like a displaced person in a poorly lit bus station.

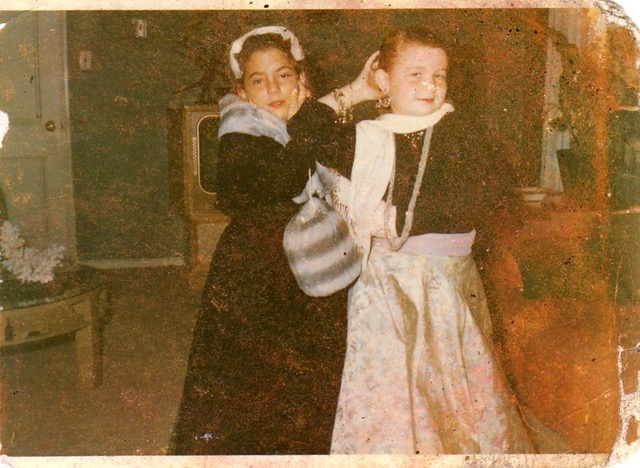

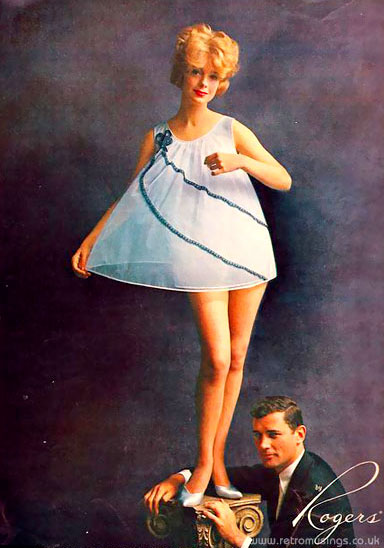

Then, as months went by, boredom reigned and some new threads held the promise of diversion. When admonished by my dad for spending more money on what he called glorified pajamas, she countered: “Why do you think we call them bed clothes, Bill?” She managed to make everyday an excuse to dress up even if only she reveled in the appeal. Actually, that’s not completely accurate because on occasion she would find matching peignoirs for us to loll around in. These uber-feminine, often translucent delicacies were two-piece nighties…a negligee and a coordinated, if useless, robe. My mother was never without her undergarments, as far as I could tell. Always, decorously presentable, she nonetheless sometimes lazed around like Carole Lombard; as her mini-twin, I looked like a child bride. Did you see Brook Shields in “Pretty Baby?” The peignoir phase spilled over to the baby-doll stage – just for me, of course. Mine being the desexualized version of the otherwise risqué originals.

As my mother’s strength returned, or should I say, when the year was up (she never actually got stronger or healthier) it appeared that she enjoyed—or acclimated to–lounging around the house. Her bedroom ensembles were worthy of Gloria Swanson’s delusional encounter with Mr. DeMille. Emerald green satiny pants with a brocaded, mandarin-collared jacket was one such flamboyance. There was a paisley ¾-length light-weight coat worn over lavender-colored capri pants that worked well from day to night. But, the luscious and delicate white dotted-swiss two-piece set, the buttons of which were covered in the same fabric, made me almost hope that I too would inherit a serious heart condition if it meant I could wear these outfits one day.

While her stay-at-home wardrobe seemed to vanquish, at least for a few hours, my mother’s increasingly forlorn emotional state, she had other needs that weighed down her psyche and could not be addressed on her own. That is, she was told not to lift her arms above her head. What does one do about one’s hair? Unwilling to cut her prematurely grey hair into a manageable yet stylish coiffure, she trained me to fashion a reasonable chignon. Wispy and unruly, her hair was no match for my 8-year-old talents, and she complained to me that she was beginning to look like Jesus Christ on the cross. Perplexing to me because as Jews, Jesus was never a talking point in our home. A confusing reference to me at the time, I sought further knowledge in the Google reference of that time; I rummaged through our World Book Encyclopedia volumes. To look in volume “J” or “C” ? Did Jesus’ hair look different depending on his situation? As I find myself today going for a deep dive into the rabbit hole that is Facebook, the green-and-white trove of knowledge was irresistible. One minute, I’m looking for information on Christ’s grooming and the next thing I know I’m focused on the C-volume’s mesmerizing display of the color wheel. Illustrations of the crucifixion did nothing to inform my understanding of how my mom related to her thinning hair. What I did uncover, however, in the W volume of the encyclopedia was more like it: The Duchess of Windsor, Wallis Simpson, and my mom were obviously separated at birth. My mother shrugged off the comparison to the notorious royal agreeing only with the Simpson’s too-true statement that one can never be too rich or too thin. My mother added…or too healthy.

With her increased stamina, my mom required a more functional outfit for her life in limbo: intermittent bed rest and the occasional but hope-inspiring visit from one of her girlfriends. What outfit says both, “I’m not healthy,” and “Who wants a cocktail?” In abeyance, my mother donned a housecoat that spoke volumes with its casual yet festive look. It was as close to ironic dressing as, say, wearing her huge sunglasses when it was raining. She wore her housecoats with stockings held in place by her girdle’s garters. It could have been that in order to pull off a sophisticated look, she felt like the person she used to be…in control of her life and powerful. There’s nothing like a whale-boned corset to make one feel held together. To avoid comparisons with Moms Mabley, my mother never once owned a floral housecoat. These were the stay-at-home jaunty frocks that must have given her a fleeting sense of the optimism. I think it must have been the absence of a waistline that somehow mitigated the possibility of slovenliness and transformed her into feeling presentable for someone who was on lockdown.

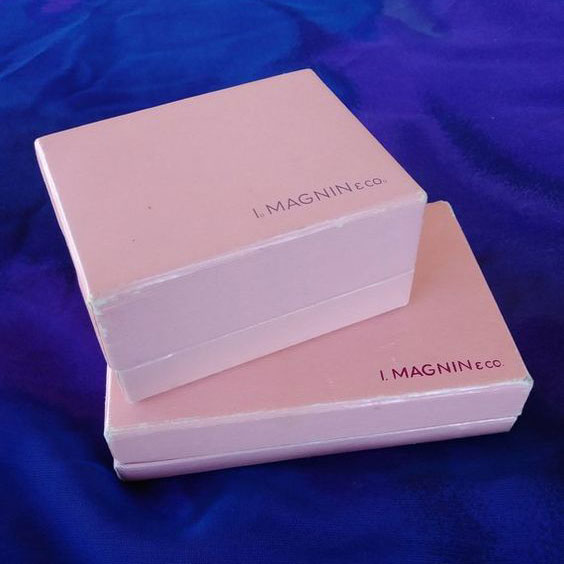

On a sunny Saturday in February, the mailman handed me a package for my mom. But she had died the day before. My dad asked me to open it and proceeded to excuse himself disappearing into his grief. There, wrapped in soft pink tissue paper, was the most beautiful and feminine of all the housedresses I had ever seen. The dress was made from clouds. The material was soft and velvety-white with a lavish embroidered trim on the placket—from the mandarin collar to the hem. The buttons were delicate, simple pearls that seemed to float on the front of the dress like tiny dollops of whip cream.

The next day my father emerged from his bedroom and asked if I could manage helping him with one necessary task prior to my mother’s funeral. He wanted me to pick out what she should be buried in. Tough decision for any other 13-year-old girl maybe, but not for me. My choice was obvious and respected by my father: she would be interred in a shroud fit for a woman, hand-picked by the wearer herself, who could pull off even the most extravagantly glitzy bed clothes. I found the perfect pair of high-heeled slippers to accessorize her outfit.

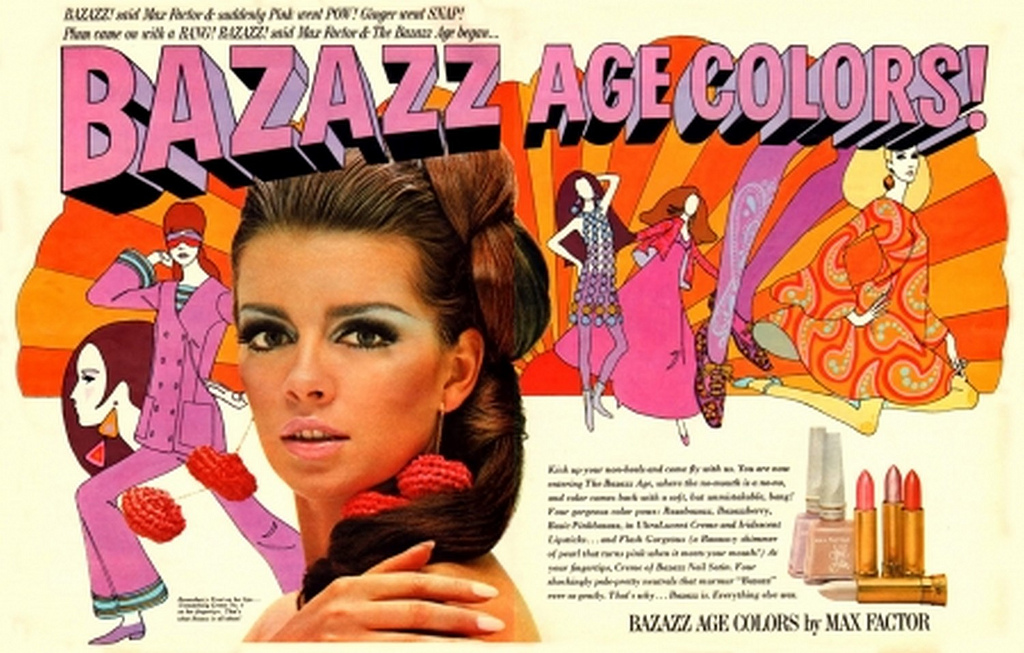

By the mid 1960s my personal choice in nightwear was the Lanz Nightgown. These cuddly nightgowns were so popular that there were entire stores dedicated to the line of sleepwear. My favorite was the small shop on Maiden Lane in San Francisco with wooden floors and circular, revolving racks from which the sweetly patterned nighties hung. The innocence of the fabric’s designs on pastel flannel…tiny flowers, sweet honey bees, whimsical stars and moons…the lace trim on the bodice, the teensy bodice buttons looking like Candy Dots and the floor-length hems belied the very essence of that free-lovin’ decade. In the days of slumber parties, now called sleep overs, my crew brought their sleeping bags, flashlights, red vines, and Swedish fish to the party; some even remembered their toothbrushes. Lanz nightgowns were our evening wear of choice. All my friends and I were missing with these enveloping nightgowns was a chastity belt.

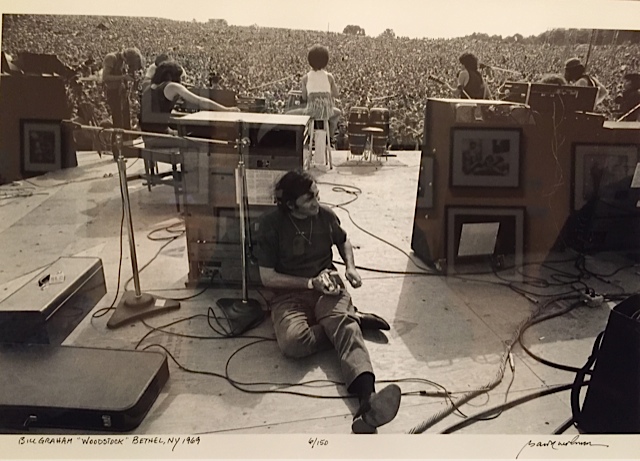

I moved on from my cozy Lanz evening uniform to oversized men’s tee shirts and hearty bathrobes that were more often than not terry cloth with pockets large enough to put a textbook or two in. These were days of co-ed dorms and shared bathrooms. No one needs ever to wear a nightgown or robe that has the potential to touch the floor of a co-ed bathroom.

A couple of years ago, I bought each of my small grandchildren their own bathrobe and they looked at me as if I had lost my mind. Such a superfluous and therefore ridiculous-looking sweater/coat, grandma. That’s what I imagine was going through their little noggins or perhaps it was the voices of their robe-less parents. But, I’ll keep trying to indoctrinate them to make peace with their genetic predisposition to dressing up for bed.

After entertainer Billy Eilish won 5 Grammys this year, her photo appeared in the New York Times. First, I had to figure out who the hell Billy Eilish is and then I took a good long look at that photo of her. She performed in what the paper called, a purposely baggy outfit. You can’t fool me, though. Those were pajamas she wore on the red carpet. I never doubted my mother’s fashion sense nor her exquisite prescience. My mom, would have applauded Eilish’s fashion statement. After all, the outfit was designed by Gucci.

Sleep Tight,