“Those damn Shapiro girls,” my father said as he drove my mother and me to one of his sibling’s Oakland homes on a Sunday afternoon. “Why don’t those pushy women let my brothers drive through the tunnel to come see us for a goddamn change?” he asked no one in particular. Sitting side by side by side on the front bench seat of my dad’s brand new 1960 powder-blue Cadillac, with the champagne-colored leather interior, my mother indicated to me with an elbow to my ribs to turn up the volume on the car’s radio.

I could see why these old people I called my aunts and uncles would fear any excursion through an ominous bore drilled into a mountainside just to get to unfamiliar and often roughly paved roads. Never mind that their baby brother, despite being in his mid-50s when I was a young girl, abandoned the urban known for the wild west of fenced-in backyards that staked off one yawning suburban patio from the one next door. He was the one who blazed new trails; not them. Let him make the drive. Plus, there were hardly any Jews on my father’s chosen side of the tunnel, and what the east side of the mountain lacked in Jews it made up for with bothersome insects and heat. As a result, two of my uncles and their wives, rarely came to visit us; so we periodically shot through the Caldecott Tunnel rolling up our windows once we were through to guard against the unpredictably cooler climate and the equally sketchy city denizens. To my father, these inner-city dwellers were much more worrisome than the bugs in our backyard.

The Shapiro girls were my two big-boned aunts who were somehow related to each other. Somebody’s cousin married someone else’s relative back in the old country and nobody ever thought twice about it. Presumably, they felt lucky to have escaped with their lives—even if their genes were co-mingled somehow. The Russian Jewish population was rapidly being murdered; who could afford to be choosy about marriage proposals?

My third and eldest Oakland aunt on the same side of my father’s family was a runt of a woman especially when standing shoulder-to-boob with her sisters-in-law. The two Shapiro women each lived in their small houses crammed with overstuffed chairs and sofas, most of which were upholstered with heavy and darkened-by-wear brocade. As if further embellishment were necessary, silky fringe dangled like neatly trimmed bangs from the seats of the furniture to the floor. I warded off incessant boredom during these afternoon visits lying prone on top of a deep-piled musty-smelling carpet and passing my fingers through the gaudy trimmings like a kitten with her play thing. From this vantage point, I could see my aunts’ thick ankles and the hemlines of their mid-calf housedresses. I could hear the ice tinkling in their high-ball glasses. Depending on the time of day and the corresponding meal being served, their dresses might be hidden behind elaborate and flouncy aprons—the pockets of which always held their handkerchiefs.

Deposited, as I often was, for a night or two at one or another of the aunts’, we had projects that were in stark contrast to those of my mother’s sparse domestic activities: sewing doll clothes, for example, or making borscht. These were day-long escapades into an exotic domain (Aunt Teresa) filled with pungent and unfamiliar odors and elaborate china plates and bowls (in the case of borscht, applesauce, or tzimmes). The doll clothes we sewed were miniature creations of my Aunt Betty’s and resembled her own fashion sense—or lack thereof. My beloved Barbie Doll, with her pointy boobs and negligible waistline looked oddly like a drag queen in her homespun shirtwaist floral dresses and shapeless housecoats. Barbie was mercilessly spared the fussy aprons.

No matter what we were up to, however, my aunts never removed their enormous gold charm bracelets that clanged like dissonant wind chimes when making the slightest move from borscht bowl to kitchen sink or from sewing machine to the nearby TV dial. Hanging from these clunky links were all sorts of charms the size of salad plates. These were mementoes of trips to the sea (an oyster shell with a pearl inside, larger than the shell itself) or to the mountains (silhouetted trees with pearls festooning the golden branches) or to Las Vegas (tiny slot machines, where pearls replaced 3-across cherries). More than once, I worried about these bracelets like a knight might fear an oncoming lance. Swung at a certain angle and velocity by one of my aunt’s pendulous arms, a hefty charm could knock out a tooth.

Damn, those Shapiro girls could really rock big jewelry. They were my early mentors.

There was one aunt on my mother’s side with whom I spent less time visiting but more time studying. Her look was iconoclastic from her ice-white wispy grey curls raked up from the nape of her neck to form a nest on top of her head. Jewel-studded combs held the semi afro in place. Her nails were painted apple red except for the half-moons nearest the cuticles and the pointy nail tips. Never a chip of polish; never a hangnail…these slender fingers caught your eye for their artistic flair and wonderment about why anyone would take the time for this odd manicure. It really was hard to look away.

Her knitting was legendary, and possibly because she was one of only two of my aunts born in the United States, and not in Minsk, she had spent easy days perfecting her skill. She was not a cook nor a housekeeper. She never wore a housedress nor a shirtwaist nor an apron. And, all her jewels hung around her neck so as not to snag the cashmere yarn of a sweater, or full-length coat, or shawl that she was constantly knitting for her sister, who was my mother. The ropes of pearls, though luminescent white and pale in comparison to the color of her hair, were silent displays of elegant accessorizing unlike the Shapiro girls’ gaudy and clamorous collections of jewelry.

Grace, this prolific and mesmerizing craftswoman, had another sister too. But, this aunt I never met. She died before I was born. Had she been alive she never would have visited us. Despite her own Jewish ancestry, which was kept as a furtive and filthy secret by her own parents, she was ironically so anti-Semitic that once her sister was married to my anything-but-closeted Jewish dad, the relationship between the two women imploded. There’s nothing like racial prejudice and hatred to dampen the mood of a family dinner.

While the Shapiro aunts were doting—wet kisses with left-over lipstick stains on my cheeks–Grace was in a class by herself. She was all discretion and elegance, soft-scented powder instead of the cloying, thick Shalimar perfume the Shapiros favored. She gifted me pale-colored nail polish and porcelain jars of cold cream, both of which my mother confiscated. Once my mother had died, all bets were off, however. I got to keep her gracious gifts, and Grace replaced the knitting projects for my mom with ones for me. A woman who despite her age and visage understood the decade in which her niece was now floundering as a teen; and she macraméd plant holders for my room and crocheted mini skirts in neon colors. But her real value in my life had nothing to do with the needles she held in her garnished hands but the comfort and company she provided.

In those early days after my mother died, Grace would drive an hour or more to be at my home when I arrived there from school. She kept herself busy and extremely useful: Food was bought, the table set, and the washing done. And then one day it wasn’t—none of it. Three short months after her first day as my doting, there-when-I-needed-her aunt, she disappeared from my life. I found her explanatory note taped to my bathroom mirror. In her flowery handwriting heavy with curly inky sweeps, she wrote that it was too sad for her to see me every day. Each day with me was a painful reminder of how much she missed her sister, my mother. The drive was too arduous for her weakening vision and the Buick’s balding tires; the housework was too exhausting, the chores too numerous, and my father was not adequately grateful. She said she would be moving to her former home in the Midwest and once situated she would write to me again.

I would have much preferred a knitting needle stuck into my eye than to have received this notice conceding her defeat. The only other adult I could absolutely trust, other than my father, had vanished and what was worse, she seemed to blame us. Abandonment is one thing, but avoidance is quite another. She could write to me if she liked. I was never–not ever again–going to let her into my heart. She could try in vain to crochet me a granny dress and matching headband for my excursions to Golden Gate Park, but I would refuse to wear them. Unless they were totally cool. It’s hard to say.

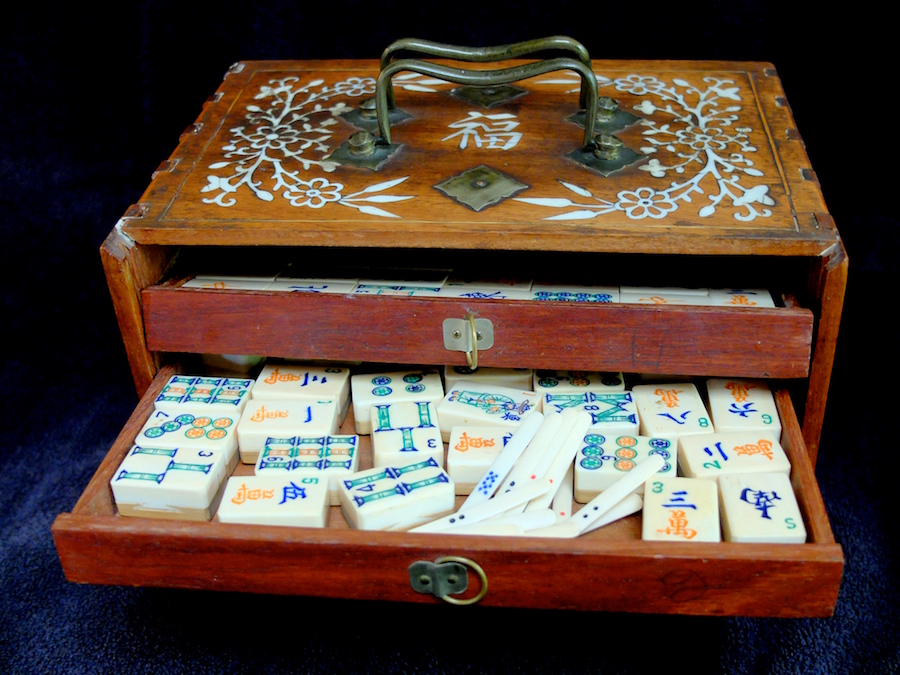

Over a decade later, with still no word from Grace, I received a letter from a cousin of mine whom I had never met. She invited me to her Sonoma home for lunch and a chance to meet each other for the first time. This woman, about 20 years my senior, was the daughter of the asocial aunt I had never met. Extremely cordial and welcoming, as if making up for the poor choices her own mother made, she brought me into her dining room. There on the massive dining table that was laid for lunch was an ornate wooden and ivory-inlaid (whoops!) box, which my cousin indicated was a Mah Jongg game set. It’s funny how the brain first tries to make sense of incongruity before relinquishing that futile effort when things just don’t add up. Why was this exotic box near my plate? Where was hers? Was this the centerpiece that just hadn’t been properly centered? My cousin invited me to sit and then to open up this elaborately constructed yet totally unfamiliar box. It was she who tried to explain the how the game was played and therefore why it housed intricately carved tiles and other esoteric objects—all of which were mysterious and confounding. I was losing patience and running out of pleasantries when my cousin instructed me to open the bottom drawer of the set. There, among the numerous carved tiles, I found a yellowed piece of paper with that undeniably recognizable and trauma-inducing handwriting. It was a note from Grace. She must have placed it inside the box; did she also leave a clue someplace else as to the note’s whereabouts? Was this a message meant to be found or was it just a way to get something off her chest and into a tiny wooden one? My cousin said she had found the Mah Jongg box among Grace’s possessions after my aunt’s death. Her death, by the way, was news to me.

I opened the tightly folded note and read:

March 11, 1958

Dear Darling Daughter,

That is correct. I am referring to you as my daughter and not as my little baby sister. That is because I gave birth to you in 1913 and yet you were raised by my mother to believe you and I were sisters. I was only 18 years old when you were born. I was far too young to raise a child and I was not marryed [sic]. I became pregnant when I worked as a stewardess on the ocean liner–the Mauretania. I fell in love with a handsome but married man—a scoundrel it turned out– who was a first-class passenger on a voyage to the Orient. It was he who gave me this box as a present. But, he never knew the real present he gave me was you, my dear child.

I wanted to tell you this story and always thought one day I would. In person, as a mother should tell her own daughter something this enormous. But I have failed to do so as yet. No one except my own mother (and the mother you now must understand is your grandmother) ever knew the truth. When you read this, please forgive me if you can find it in your heart to do so. Maybe one day, when you are much older and have experienced much of the world, you will be able to sympathize with the choices I made. Citing my youth as the reason for my actions you might think is suspect. I meant you no harm. Just the opposite, in fact. I felt I had no choice and received no guidance. But these are poor excuses for keeping secrets.

All my adoring love,

Your mother, Grace

Lunch was served; my cousin pushed Exhibit A away from my plate and began to scoop heaps of food in front of me as a means of diversion. But there was no way for me to simultaneously eat and make any sense of what this seemingly innocuous box had coughed up.

My mother never saw this note, of course. Grace’s weak attempt at reconciliation and her pitiful explanation whizzed right past the intended reader as life took an ironic and unfair detour. Instead, the news landed on the lunch plate of her unsuspecting granddaughter. The pain Grace must have suffered from the loss of the child she could never claim was undoubtedly surpassed by the anguish of withholding the truth once again. What was the point of her secrecy, I wondered? Although the answers I now conjure up are filtered through the lens of modernity—our current era’s worship of the total reveal–for better or for worse. It’s hard to keep any secrets anymore.

The high seas and the floating cities that traverse them have always fascinated me but never enough to succumb to their claustrophobic lodgings. The sense of being held captive is unnerving. My grandmother formerly known as my aunt must have had the conflicting sense of freedom from the tethers of her contemporary society’s morals and the unmitigated shame of knowing that her actions resulted in duplicitousness whose rippling effects created more than waves–more like a tsunami—in a family that was never again to be whole.

All ashore that’s going ashore,

![]()

Wow…. What a story! Beautifully written, it begs for more detail about how the family was impacted over time. Thanks so much for sharing it, Naomi, and hope we can learn more.

BTW, I have a treasure trove of detailed old letters between my Mom & Dad when they were courting immediately after the war (he working as a social worker in the United Nations refugee camps in Germany, she as a newly-minted teacher of typing and shorthand in Hells Kitchen and Harlem). They met at the Jewish USO in NYC while my Dad was on break half-way through his two-year assignment. Reading your story reminds me that I’m overdue to start reading these letters and see what I find.

Hugs, Judy

Thank you for writing, Judy. What wonderful comments you shared. I urge you to check out a podcast called Love Letters Live by Janet Gallin. Perhaps you even know her? Her premise is all about the importance of letters – real letters. Lovely to hear from you! XO

Your story is gut wrenching. So much pain and trauma. I’m so happy that you grew up , married Marty and settled in Marin County.

Well, Steve, the good news is that while I was actually experiencing these childhood events I processed them through a filter of denial or distance or something. I really didn’t experience my childhood as either traumatic or painful at the time. As for growing up, hmmmmm? Not sure if that has happened yet.

All kidding aside, I am so grateful for your comments. They mean a lot to me. XO

I didn’ t see that coming. You wrote it so well, just the right amount of subtle set up and then “pow” ! I was a couple paragraphs ahead of Steve on my device and I gasped out loud when reading the letter. That’s quite some childhood you experienced. Love Jan

Thank you, birthday girl! I’m so tickled that the blog grabbed you. I love, as I always do, hearing what you have to say about my writing. XO

This is a riveting story, and I assume it’s true. It has the makings of a wonderful novel!

Thank you so much, Melissa. I really love hearing what you have to say about my writing. Wouldn’t that be grand to start a novel? That would require a house in Inverness with a view, I think 😉

Wow, good to hear your “voice” again in your writing. This is really a great story! My family on my mother’s side had all kinds of secrets, so I can relate. Hope you are doing well! I’ll explain my absence shortly.

Lovely to hear from you, Susan. I know you have so much going on right now and I sure appreciate you taking the time to read my blog…and then to comment also. Means the world! XO

Gevalt and geshrigen my darling Naomi, is there no end to your amazing family background. Such a riveting piece and written with such perfection! I’ve forwarded to Miriam, I know she will love reading this. But our pleasure today was your pain to deal with and process. Thank you again for your fantastic writing, which I love, as I love you xxxx

Thanks you, dearest Hadassa. If you were in the same kitchen as me, I’d make you my version of borscht! Although, undoubtedly yours would be better. I appreciate your support. Give Miriam my love!

XO

Your family history is intricate and fascinating beyond any I have read in fiction…such a memory you have, unbelievable.

Can there be more?….

Can’ t wait.

Valerie

I love your comments, Valerie. It’s not everyday somebody admires my memory. Who are you again??? XO

“To survive, you must tell stories.”

—Umberto Eco

It seems clear to me, my dear and very talented Nomi Girl, that within this blog you have planted the seeds for your first novel.

I’ll grind the beans and brew you up a fresh pot!

XO

Yer Jules

Dearest Umberto, your wise words are of great comfort. Thank you for sending them along.

Beautiful. So many secrets in every generation. You captured it with such poignancy. Would that we could know…Bravo! I see a screenplay… Can’t wait to catch up…! xox, Sv.

Thank you so much, Svetlana, for taking the time to read and comment. I agree…secrets are everywhere. It’s the stuff of blogs, it seems.

Sorry for the delay in responding to your lovely note. We were away…XO

Oh my goodness. If only there were a way to go “back”. I remember you as Dr. Sinai’s beautiful, spunky little girl with the red hair. I know my mother took to you quickly for your intelligence and potential, not to mention her fondness of your parents. I regret that I was not younger or you a bit older in order to have facilitated our becoming childhood friends. We were six years apart. Every family has stories; certainly mine is no exception but reading yours was quite an adventure in going back in time and recognizing and relating to so many details of a life that was, indeed, a lifetime ago. I so wish I could have spared you some of the trauma of losing your mother or even being that “sister” that you could confide in. I wish I had known; that, I regret.

Dear dear Barbara. Please excuse my delay in responding to this most incredible comment. I am going to send you a private email in response, in fact. Let’s just say, that I really and truly do remember you primping for a date or for something fun and wishing that I could be you. When would this have been, I wonder? Perhaps you’d like to subscribe to my blog? I write more and more infrequently (like once every few months), but they posts do tend to be about my life growing up. I’m so happy we found each other!