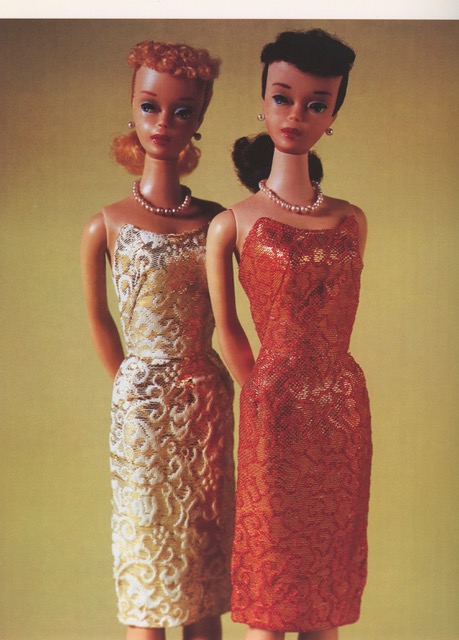

I grew up in a golfing family. By family, I mean my parents who both played the game. I, however, preferred amusing myself with my Barbie dolls any chance I could get. This included bringing Barbie, and often a reluctant Ken, along in the golf cart when I was made to accompany my mom and dad to the course. On the very rare occasions I was allowed to remain at home, which was during their rounds of twilight golf on Friday summer nights, I not only was left to play with my dolls but also to enjoy my favorite meal of all: Swanson’s fried chicken TV dinner.

I loved Friday nights.

On Sundays, however, our family time was spent on the golf course. Our family vacations revolved around visiting and playing golf courses up and down the state of California and the very rare excursion to Hawaii. I was always encouraged (nagged) to pick up a club, be it wood, iron, or putter and play a little. Word had it, according to my father, that I had a natural swing. I’m not sure how natural it is to try and wield in any semicircular shape a bottom-heavy, adult-sized club, but I apparently was pretty good at it. And, I could see how much pleasure both my parents derived from this sport. But no matter how much swinging and swaying, or even exuberant raking in the sand trap after someone’s ball took a bad turn and ended up in said bunker, I couldn’t fathom the sport’s appeal. As soon as we arrived home again and congratulatory cocktails were mixed and poured for the adults, I would head back to my room and pick up my dolls to once again inhabit my magical world—a universe where I was in complete control. Here I pretended I was the adult. An adult who had no desire to play golf. My Barbie Dream House was irresistible and Barbie was the flawless denizen in my neighborhood of make believe. It’s hard to compete with perfection especially as I imagined her to be.

The fresh air, the verdant and soft-squishy grass carpet underfoot, the sounds of metal cleats treading on the pavement around the pro shop, the myriad of golf-bag zippers being dragged opened and closed, that luscious wet suction sound of the ball cleaner gizmos found on so many holes all were diverting but never as exciting to me as what happened inside the clubhouse. That was where I could understand what all the fuss was about. It was inside the ladies locker room, for example, where I met the three B women who became for me the most significant women in my life once my own mother had died. Mrs. Burton, Mrs. Brenesell, and Mrs. Barnett as a triad embodied the characteristics of my ideal and, unlike my Barbie doll, very real woman.

Mrs. Burton, also named Evelyn as was my mother, seemed unflappable and composed. She could deflect her disappointment of an upsetting score on the course with a modest giggle and the sweep of her hand. She also had covetable earrings in the shape of sea scallops. Obviously, she had a flair with accessories. And, she was the one I would choose much later on–in high school–to show up at school when events required the presence of one’s mother: the occasional tea or fashion show come to mind. Evelyn also had a son, five years older than me, whom I was certain I would marry. My imaginary narrative spun this tale: Marriage to her son would cement my relationship with Evelyn assuring me that she would remain in my life forever. She was the kindest woman I had ever met. I was not going to lose this Evelyn.

Mrs. Brenesell, Vera, was the genius of the group. She tutored me in math and science and her home was ultra modern by 1960 standards. Split level with teak floors and a dining table set with Heath ceramics (even at Passover Seders!), what she lacked in fashion sense she made up for in home décor. Her vibe was cool and austere. She was logical and humorless but her refined, buttoned-up demeanor and unusual, halting speech patterns reminded me of Katherine Hepburn without the flared trousers. Tuesday night tutoring in her Berkeley home was a weekly occurrence that helped me progress in math and, more critically, gave me a few hours of womanly companionship and oddly intellectual stimulation that I could depend on. She was steadfast and committed to my growth and development as well as my grade point average.

Ellen Barnett, I always thought, was my mother’s best friend of the bunch. Her voice was froggy like Blythe Danner and her hair, loose salt-and-pepper strands unsuccessfully held in place by tortoise-shell combs, replicated the 1960s vibe with its loosening of waistbands, bras, and mores. On her wrists were clunky, Bakelite bangles in tequila-sunrise shades of reds, oranges, and ochers that she nervously toyed with by pushing them up toward her elbows or down toward her wrists. She seemed unconcerned with her jewelry banging into the pots and pans while cooking; she wore them while she weaved her magnificent wall hangings that included not only fibers of differing origins and colors but incorporated utilitarian items like wooden spoons and chop sticks or decorative adornments of feathers and beads. Her loom sat inside her craft room that had cathedral ceilings with wooden beams and a burnt-sienna-colored shag rug on the floor. She was the artist, the bohemian, the renegade whose house sat on a gnarly boulder the size of an army tank. It was Ellen whom I called first the night my mother died.

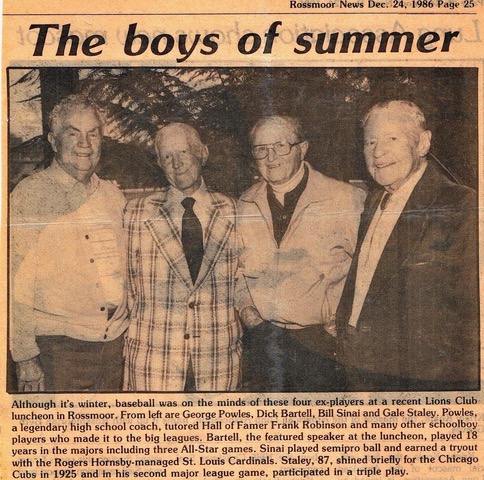

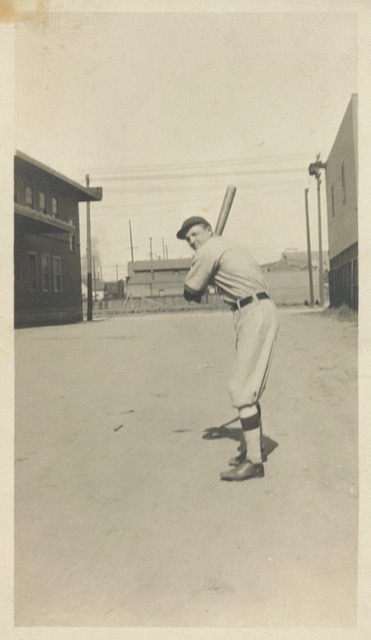

My father, however, introduced me to the pleasure of making friends. He could work a room like a master of ceremonies at a Friar’s Roast. He had a joke for every occasion and a personalized one for nearly every guy at the bar. He was happiest when he was at the club and happier still when he found the golf club that epitomized his having made it as an assimilated American Jew. A gifted and coordinated sportsman, who at one time paid for his education by playing professional baseball, he was now a paid-in-full and dapper member of the landed gentry. Or, at least he liked to think he was.

We lived about 3 miles from a gorgeous, stately course surrounded by fabulous homes with picturesque, well-tended gardens and long, gravel-strewn driveways. Driveways that were circuitous and inaccessible to folks like my family. The country club was restricted, which was code for: No Jews; No Blacks. Probably “No” to a lot of other folks, but those were the two groups of possible infiltrators whom people seemed most worried about at that time. Not being allowed to join the nearby course was one reason my parents became members of a club much farther from home. Eventually, a new club would be built nearer to our home, and it was there that I witnessed my father’s sheer joy at having a place feel as comfortable to him as his house. After my mother died, he and I would go to his club for dinner twice a week; he would see that I was sequestered in the clubhouse or at the pool while he finished a round of golf. Then I would do my homework in the clubhouse lobby while he had a drink with his friends or took a lesson from one of the club’s pros. The caddies were all cute boys from high schools other than my own, and so there was the added advantage of honing what pathetic flirting skills I had while not suffering the repercussions of being rebuffed–which I usually was. I always completed my schoolwork because I saw little action as a result of my listless feminine wiles.

As a teenager, I took great pleasure with my friends in tearing up the fairways of that anti-Semitic club close to home—the one that refused membership to my father and his ilk. Friday or Saturday nights a group of us would purchase blocks of ice, wrap them with towels and ice slide down the velvet, tractionless swaths of green grass. Dodging healthy doses of water from automatic sprinklers while inhaling other forms of grass or imbibing grain-based beverages, we slipped and slid and occasionally dodged the police when they were called about the rowdy, disrespectful kids. I once mentioned this activity to my father assuming he would find it fair retribution for his being ostracized. Instead, he found my actions reprehensible and unsportsmanlike. From then on, I never divulged to him my participation in anti-war protests that I was attending with more and more regularity. No ice at those assemblies but plenty of grass.

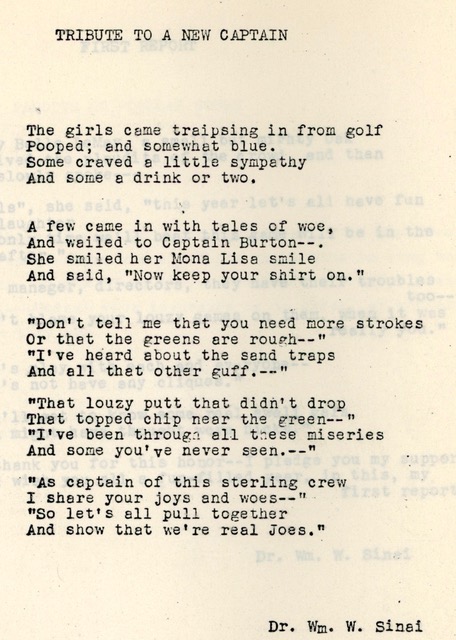

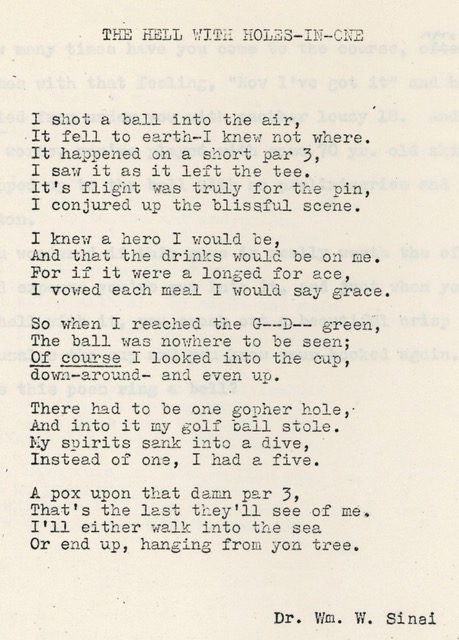

My father, a dentist by profession, had a penchant and a real talent for writing poetry—more specifically rhymes. His work defied classification because the work had the passion of an ode and the humor of a limerick. The poems were always personalized; my father would write about Joe or Joan, who recently broke 100 on the course. Or, as a man of his time, he would rhyme about how his wife neglected her homemaking duties to beat him at a game of golf. His favorite subject, however, was himself. He would preface a poem’s recitation by saying something about his golf game never improving; it only got verse. He wrote hundreds of these and he frequently published them in the club’s newsletter or he recited them at the scores of social events held at the course – a tournament, a round robin, a crab or spaghetti feed. The poems were so popular and so plentiful that my dad engaged the work of a cartoonist to illustrate the words and created a book (which remains unpublished not for lack of his trying) for his own amusement. Incidentally, he did the same with a book dedicated to bowling (!) and one for tennis. My own lack of enthusiasm at the time regarding this tome had to do with the countless hours I spent typing and retyping and then typing once again each and every poem. Every time the poem was adapted to commend someone else shooting par or commiserate about missing a putt or losing the ball in the rough, there were no cutting and pasting. There wasn’t even white-out. The poem was retyped. His secretarial support consisted of me, our typewriter and two white sheets of bond sandwiching a piece of well-worn carbon paper. There was always a last-minute deadline that had to be met. As my father’s girl Friday, I was behind the scenes and the silent but always reliable assistant. He was forever grateful for my skill set and what he supposed was my enthusiasm. I did it because it made him happy. And, if I finished typing them quickly, I was even happier.

And, then, one day about 5 years ago a new friend came into my life. She grew up in a house adjacent to my father’s country club. Her parents were also members of this golf course, and we suspected that our parents must have known each other. All of them, her parents and mine, were gone now but she had retained oodles of memorabilia from those days of their membership; I had not. She brought me a newsletter that had a photo of her exquisitely attractive parents on the cover and inside there was a poem by my father. The pleasure it brought my father while he was writing that poem, the happiness I felt typing it for him, and remembering his glee when he saw the poem published was not unlike the pleasure I have sending out this and every blog I write. I even get to type it myself–without having to insert a sheet of carbon paper in the printer.

It’s not about the love of golf that my dad imbued in me; he allowed me to witness the pleasure of making others happy and how satisfying that can be.

That’s the sweet spot,

![]()

Fore!!

See you at the 19th hole…

As someone who was blessed to know your father and have heard so many of his stories, this post was a wonderful journey with those memories. Thank you

You of course were so important in my dad’s life and in the recall of his remarkable adventures. Thanks to you, Steve, so much was retained for us. But, that’s (as they say) another story…

Nomi, this is so wonderful, thank you! My dad was a lifelong passionate golfer too! I don’t remember anything making him as happy as getting ready to play golf. And he did hit a hole-in-one at New Orleans’ City Park golf course. One of his final requests as he was dying was that some of his ashes be put in that hole in one…and we did!

Wendy!!!! That is a remarkable story about your dad whom I imagine had as much spunk as his daughter. Your story has a blog in it too 😉

Oh my, Nomi, this one is delightful, and as always, poignant. Great to meet your three “Moms” and to get to know your dapper Dad. How do those blocks of ice wrapped slide?

Oh, Kay! You’d be a really good ice slider. Remind me to show you how next time we meet! Thanks for reading the blog and for your comments. XOX

I love your Dad’s rhymes; I now where you get your firecracker humor and quick puns. I only have been golfing once in my life with Rick Lewis in Tilden in 1967. I nearly passed out from boredom….

If only you could have written some haiku on the course. You would have had something to do. I’m gonna write you a poem asap. Did you ever slide on a block of ice in Orinda????

Nomi— ah, the memories… “ice-blocking “ with you was a good one- did your dad ever know about us sliding down the laundry chute at The Claremont Hotel? Lots of slippin’ and slidin’ in the sixties. And I love Dr. Sinai’s ( just can’t call him Bill 🙂 poetry— just like I love reading your remarkable blog filled with your wit, sensitivity and compassion. And the last photo of your dad and the boys… ❤️

One thing at a time, I guess, where my dad was concerned. First the ice sliding, then the occasional war protests. But no. I never divulged the laundry chute escapades. Besides, I just drove the get-away car, didn’t I? Love that you wrote to share with me your thoughts. Very few folks can say they shared my block of ice. XOX

Love it! The photos were great too – Baba watching Nate and El pound some balls. 🙂

Those little guys coulda been contendahs!

Thank you, Lenny, for your sweet response. See you real soon!

XO

The writing is brilliant. I loved the descriptions of the barbie dolls, three B moms, typing dad’s ditties, ice sliding , and your parent’s love of golfing. I especially liked your recounting of your attitude towards the whole scene. You had a lot of pluck. It took me back to my childhood ,when I watched my Mom golf at the Waveland golf course back in Chicago. Life seemed so different from today. Thanks for the stroll down memory lane. xoxo Steve

Oh, Steve! What a lovely response. Thank you very much. I had no idea, of course, that your mom played golf. This entry seems to be jogging quite a few memories for folks. I love hearing from you and appreciate it more than I can say. XO

Delightful, Naomi! I’m no golfer, and neither were my parents, but my uncles played. I could definitely relate to the Barbie escape and the Swanson TV dinners, when my folks were out playing bridge and poker.

I’m writing you from Aguas Calientes, Peru; will be climbing Machu Pichhu Mountain tomorrow. Thanks for sharing your story!

Oh my goodness. We speak the same language, sister! Climb every mountain down in Peru but be careful of that altitude 😉 I am very, very honored that you took the time to write to me about this entry. Means the world! Take care!

You scored a hole in one once again! Brilliant! Delightful! Informative! Touching! Impressive! Eloquent! A beautiful tribute! The photo of you in front of the “modern TV” looks just like Emily……..hugs from the east coast. XOXO

You are so smart!!!! That twin sister IS Emily 😉 Thank you so much, Alice, for your enthusiasm for my blog. I am hugging the east coast right back. I hope you can feel it! XO

Ahh Nomi, what a wonderful pice of writing. I enjoyed reading it hugely! Kisses Hadassa

Oh how lovely to hear from you! Thank you for your beautiful response to my blog. BTW, I just sent you a brief email too 😉 XO

Nomi – You are a gem! Evelyn Burton, one of the three ladies you mentioned in your blog and one who had filled a void in your childhood following your mother’s passing, was my remarkable mother. Had I proposed to you, that gorgeous little red-haired girl five years my junior and still in elementary school, and had you accepted, we could have taken off in a golf cart while your dad and my mom ran behind us trying to make sense of our elopement. C’est le vie.

Your Evelyn and mine (I mean my very own maternal version) were stellar women who must never be forgotten. And, having you, Steve, in my life again is just the best way I can think of to pay tribute to them. Thanks for your beautiful comments. And, please, go back and read one of my dad’s poems, obviously dedicated to your mom. Did you notice? XO

Golf? I am amazed. Had no idea you were a golf brat. Love the poetry and descriptions of the three B’s and, of course, your father.

What an amazing childhood you had! Seems your father really stepped into it with you to coach. Too much!

Thanks for sharing as they say somewhere.

Love and hugs,

Vslerie

Well, I was a brat of many stripes! Thank you for giving the ol’ blog a read and for your wonderful, pithy comments too. I am ever grateful for your expert eye as a writer/reader. XO

Hey, Naomi, interesting read! My parents, too, were golfers & loved the scene after a round in the clubhouse. Given their enthusiasm, I tried taking golf lessons as my PE requirement at Miami U. in Oxford, Ohio my freshman year. It was a whole semester 2 days a week for an hour & a half. NOT MY GAME! It was so slow that I thought I would lose my mind. Was never tempted to touch a golf club after that semester ended…

Ha! Slow as dirt but on the other hand, speed has never been my thang 😉

I’m torn!!!! However, one thing is for sure: I am always so happy to hear from you. And, I sure appreciate your reading and commenting on this entry. Means the world to me. XO

What a treat! Loved reading your blog.

Thank you, Robin! So delighted that you enjoyed the bit of time travel 😉

Kol hakavod! How wonderfully you write. So entertaining and interesting. Your Dad sounds like an amazing man

Toda raba! And thank you for the very generous assessment of my writing. You woulda loved my dad; he was a true reconteur. Not sure how you say that in Hebrew. Maybe, mensch? XOX

Naomi- your writing is SO lovely! What a touching, sweet and funny story about your 3 moms and your wonderful dad- I totally enjoyed it and the pix too!!!

Hi Paula!!!!!! Wow! What fun to hear from you. Thank you, dear friend, for reading and then reaching out. Marty takes those photos for me.

He is underpaid, but not a word to him, ok? XO and I appreciate your thoughtful comments.

I just loved this, like all of your blogs and especially love the pics. I long for captions to tell me who is who and what’s what. Which of the three ladies are the ones in that amazing pic, styling for days, all arm in arm? I read each amazing comment and your response. Just lapping this of you – up. I look forward to your next installment.

Thank you, Jennifer. What an incredibly lovely comment you composed. It is especially nice to read as I’m about 3 miles away from you at the moment.

Wink, wink. And, naturally, longing to see you. Marty is my outstanding photographer and I passed on your comments to him too. He, like me, sends our love!

Hi Nomi, as usual I loved reading your latest blog! They always make me feel closer to you as I had not had the good fortune to share in your childhood as some of your friends had who comment about your blog. I love your descriptions about playing with your Barbies as my childhood memories are filled with loving my dolls, especially Sparkle Plenty and playing with our collection of stuffed animals with Marty! xoxo Emily

You are so sweet to chime in. You may not have been with me from the beginning, Em, but you’ve been with me for most of my life. And, anyone who adores Sparkle Plenty was meant to be my sister. The stuffed animals are another story (of course, they still linger–as you well know!). I appreciate your taking the time to both read and comment on this installment. Love you. N

“…the pleasure of making others happy”, loved it.

Maybe thats what I want my art to do to?

I will keep on reading.

Hope you are having a nice summer in California.

Lots of hugs,

from Catalina, the Chilean artist making the project “This thing is red” at the brooklyn library in Nate,s gallery.

Catalina, Hola! And thank you so much for checking out my blog. I hope you’ll have a minute to read the latest one on our trip to Barcelona most especially because of the intersection of language and experience. Just what your art speaks to…and so beautifully too (your art, I mean!). It means the world to me to have heard from you. Thank you for taking the time to comment. XO Naomi